Lessons for AI Governance from Atoms for Peace, Part 1: Atoms for Peace

This series of blogposts was co-authored with Dr. Sophia Hatz, Associate Professor (Docent) at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research and the Alva Myrdal Centre (AMC) for Nuclear Disarmament, at Uppsala University. She leads the Working Group on International AI Governance within the AMC.

Logic and Strategy

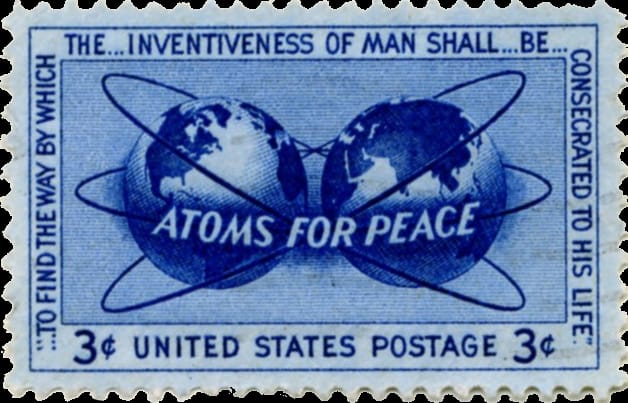

In the early 1950s, the United States and Soviet Union were locked in a nuclear arms race, each developing ever more destructive weapons. President Eisenhower, seeking to ease global fears and reframe the nuclear narrative, unveiled the “Atoms for Peace” proposal in a speech to the UN General Assembly on December 8, 1953. In this address, Eisenhower acknowledged the grave risks of nuclear war but stated an American commitment to “find the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.”[1]

At its core, Atoms for Peace proposed an international exchange: countries would forgo nuclear weapons development in return for access to peaceful nuclear technology under international oversight. This arrangement created the foundation for the eventual Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which took effect in 1970.[2] The bargain involved nuclear powers contributing fissile material to an international "bank" supervised by the United Nations, with this material dedicated exclusively to peaceful applications in energy, medicine, and agriculture. Non-nuclear states would receive technological benefits while agreeing not to develop weapons, and nuclear-armed nations committed to gradual disarmament efforts. This framework attempted to balance two competing interests: preventing the spread of nuclear weapons while ensuring all nations could benefit from nuclear science's peaceful applications. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) emerged as the primary oversight body for this arrangement.

The United States leveraged its advanced position in nuclear technology to establish credibility and leadership in peaceful nuclear cooperation. This approach included passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954[3], which created the legal basis for international nuclear cooperation, distribution of research reactors, specialized training, and nuclear fuel to allies and neutral countries, and establishment of the IAEA in 1957[4] as an institutional embodiment of Eisenhower's vision. The United States also created verification mechanisms to ensure nuclear assistance wasn't diverted to military programs. By sharing nuclear expertise under controlled conditions, the United States positioned itself as the principal architect of the international nuclear order. This technical leadership reinforced American influence in shaping global nuclear norms and practices.

Beyond its stated humanitarian aims, Atoms for Peace functioned as a sophisticated Cold War strategy with multiple objectives. It presented American technological prowess in a benevolent light to counter Soviet influence and won support in developing nations by offering advanced technology and energy solutions. The initiative reassured European allies about America's commitment to peace while simultaneously encouraging their participation in NATO's nuclear deterrence strategy. It maintained strategic advantage by controlling which nuclear technologies were shared and with whom, and created a narrative of American leadership in peaceful development that contrasted with perceptions of Soviet militarism. President Eisenhower's initiative reflected his dual ambitions: to be recognized as a peacemaker while effectively containing communism's spread[5]. The program's humanitarian framing masked its function as an instrument of geopolitical competition, allowing the United States to shape Cold War dynamics while appearing generous rather than aggressive.

Successes of Atoms for Peace

The Atoms for Peace program left a mixed legacy, but it achieved several notable successes that reshaped global nuclear affairs. Institution-building was perhaps its most enduring accomplishment. Eisenhower’s initiative directly led to the creation of the IAEA in 1957, introducing the concept of international nuclear inspections and safeguards. For the first time, an international body was empowered to monitor nuclear facilities to ensure material wasn’t diverted to bombs.

Atoms for Peace also fundamentally changed global attitudes toward nuclear energy. Eisenhower’s optimistic framing helped normalize the idea that nuclear technology could be a tool not just of war, but of progress and human well-being. In the decades following the speech, dozens of countries launched nuclear research and power programs with U.S. or international assistance. By the 1960s and 1970s, reactors provided electricity in nations from France to India, and isotopes improved medical treatments and agricultural techniques worldwide. A recent speech delivered by World Nuclear Association Director General Sama Bilbao y León to the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars noted that Eisenhower’s “one seed” of an idea grew into a “forest of possibilities” in peaceful nuclear applications—from 400+ reactors supplying clean power to advances in cancer radiotherapy[6]. While one can debate how much credit is due to Atoms for Peace versus other factors, the program undeniably accelerated the diffusion of scientific knowledge and nuclear infrastructure for civilian purposes. It made nuclear energy cooperation immensely popular and gave momentum to international scientific collaboration at a time of East–West polarization.

Crucially, Atoms for Peace established the normative groundwork for what became the global nonproliferation regime. As historian Peter Lavoy observes[7], the initiative produced many key elements we now take for granted: “the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the concept of nuclear safeguards, and most importantly, the norm of nuclear nonproliferation” as an expected behavior of responsible states. Before Eisenhower’s proposal, there was little international consensus on how to reconcile peaceful nuclear pursuits with the prevention of weapons spread. Afterward, however imperfectly, a norm emerged that countries could access nuclear technology conditionally – i.e. if they committed not to build nuclear weapons and accepted inspections. A major consequence of the proposal was also the very idea of an eventual total nuclear disarmament. These elements were later codified in the NPT (1968), but its philosophical underpinnings trace back to Atoms for Peace. In short, Eisenhower’s gambit demonstrated the value of combining carrots and sticks: offering technological benefits and international legitimacy as incentives for arms restraint. That approach has remained central to nuclear governance and offers a potentially useful template for AI governance.

Shortcomings and Unintended Consequences

For all its idealism, Atoms for Peace had serious shortcomings that tempered its legacy. Nuclear proliferation did not halt—in some cases, it arguably accelerated under the cover of peaceful aid. As some analysts[8] have noted, “it is legitimate to ask whether Atoms for Peace accelerated proliferation by helping some nations achieve more advanced arsenals than would have otherwise been the case. The jury has been in for some time on this question, and the answer is yes.” The program hastened the global diffusion of nuclear know-how, and some recipient nations – notably India, Pakistan, and Israel – diverted ostensibly peaceful assistance into their weapons development efforts. For example, India’s first nuclear explosive in 1974 was enabled by a Canadian-supplied reactor and U.S.-supplied heavy water from cooperative agreements in the 1950s. Similarly, research reactors and training provided under Atoms for Peace helped jump-start programs that later produced weapons in Israel and Pakistan. The hope had been that introducing international oversight would counteract the risks of sharing nuclear technology, but in the first decade, safeguards were weak or nonexistent. This enforcement gap meant countries could receive nuclear hardware and expertise while remaining outside any binding nonproliferation agreement until the NPT regime took hold years later.

Another shortcoming was the program’s geopolitical imbalance and resulting mistrust. In practice, Atoms for Peace became a largely U.S.-led, Western-centric enterprise. The Soviet Union, distrustful of American intentions, refused to pool any of its fissile material and dismissed Eisenhower’s plan as propaganda. Non-aligned nations in the Global South were also cautious: while many welcomed nuclear assistance, they resented the implicit bargain that demanded renouncing weapons options in exchange. Countries like India, which saw nuclear technology as a ticket to modernity and international stature, bristled at the notion of technology control by the great powers. The result was a trust deficit: some states felt the rules of the emerging nuclear order were being written for them rather than with them. This partisan dynamic undermined the spirit of cooperation that Eisenhower’s rhetoric espoused.

Critics also argue that Eisenhower’s emphasis on the “peaceful atom” carried a paradoxical message: it framed nuclear technology as the harbinger of peace and progress, yet implicitly accepted the permanence of superpower nuclear arsenals as the guarantor of world stability. In other words, Atoms for Peace did not directly pursue disarmament; it was a peace through strength and technology management, not a peace through eliminating the Bomb. This approach, which historian Ira Chernus terms “apocalypse management,”[9] normalized the indefinite existence of nuclear weapons as a backdrop for peace. One could argue it sidestepped the deeper ethical question of the arms race and instead focused on managing its side-effects.

Lastly, enforcement and safeguards under Atoms for Peace were initially too lax to prevent determined proliferators from cheating. The IAEA eventually developed robust inspection practices, but in the late 1950s and 1960s, the regime lacked teeth – there were no mandatory inspections until states began joining the NPT. Israel received a research reactor from France and simply kept it outside of safeguards, using it to produce plutonium for weapons. Pakistan received extensive training of nuclear scientists through Western programs well before any oversight regime existed. The technology outpaced the governance in those early years, a cautionary tale for any similar framework in AI or other domains. It was only after proliferation cases came to light that the world tightened nuclear rules (for instance, India’s 1974 test led to the Nuclear Suppliers Group’s formation to better control exports). The Atoms for Peace era thus teaches that a voluntary, trust-based system can be exploited if not backed by verification and consequences. Balancing openness and security is incredibly challenging: too much openness can aid malign actors, while too much restriction stifles beneficial innovation. Eisenhower’s program attempted to walk that line, with mixed results.

- Atoms for Peace Speech | IAEA

- Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) – UNODA

- Atomic Energy Act of 1954

- The Statute of the IAEA | IAEA

- Chernus, I. (Ed.). (2002). Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace (1st ed). Texas A & M University Press.

- Viewpoint: The legacy of Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace speech. (2023). World Nuclear News. https://world-nuclear-news.org/articles/viewpoint-the-legacy-of-eisenhower-s-atoms-for-pea

- Lavoy, Peter R. 2003. “The Enduring Effects of Atoms for Peace.” Arms Control Today, December 2003. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2003-12/features/enduring-effects-atoms-peace.

- Weiss, L. (2003). Atoms for Peace. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 59(6), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.2968/059006009

- Chernus, I. (Ed.). (2002). Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace (1st ed). Texas A & M University Press.